Menthol cigarettes: Attitudes, beliefs and policies

The 2009 federal law giving the Food and Drug Administration the authority to regulate tobacco products prohibited the use of flavors in cigarettes with one exception: menthol cigarettes. Menthol cigarettes — which contain a mint flavoring that suppresses coughing — are associated with increased smoking initiation and addiction among youth, are used disproportionately by young people and African-Americans and are more difficult to quit than regular cigarettes. Despite a significant body of scientific research that indicates prohibiting menthol in combustible tobacco products would benefit public health, the FDA has yet to issue a product standard to eliminate menthol. As a result, several cities and localities around the country are acting to ban or restrict the sale of menthol cigarettes. For more information on menthol tobacco products and their health effects, see the Truth Initiative® fact sheet on menthol.

Due to the health impact of menthol tobacco products and their role in prolonging the tobacco epidemic, Truth Initiative conducted a nationally representative study to better understand:

- Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to menthol in cigarettes, especially among African-Americans, who use menthol cigarettes at disproportionately high rates

- Public attitudes regarding menthol bans or restrictions

Key findings from the study show significant levels of inaccurate information and misperceptions about menthol in cigarettes among U.S. adults. The survey provides further evidence that a ban on menthol cigarettes is likely to improve public health.

Methods

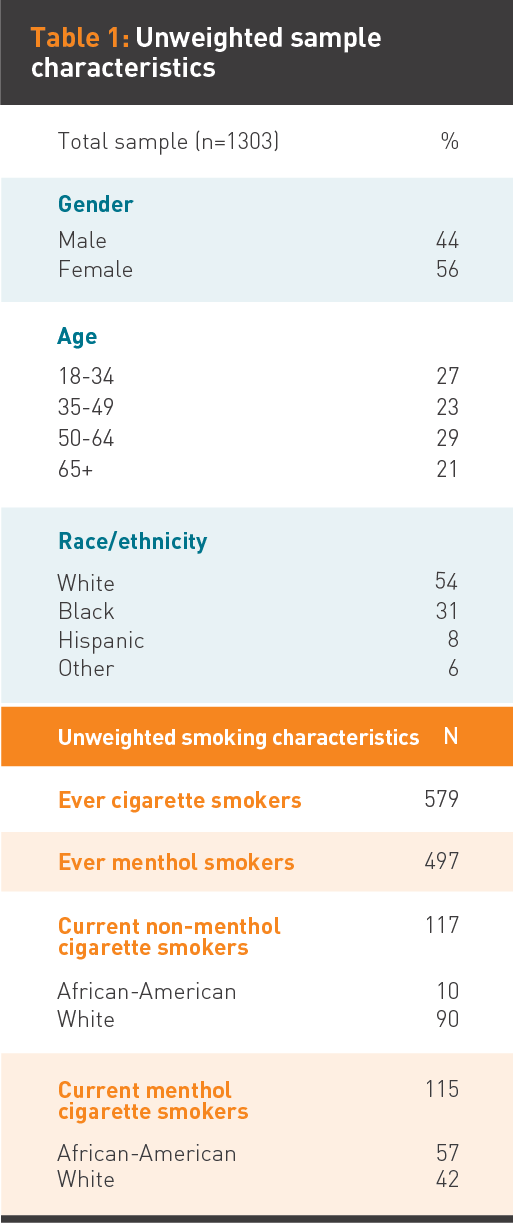

Data were collected from the NORC AmeriSpeak® address-based panel. Participants were asked to report how their behavior may change if menthol cigarettes were banned. The survey was conducted among adults aged 18 and older, including an oversample of 300 African-American interviews, to reach a total of 400 African-American interviews. Surveys were conducted online and on the phone from June 21, 2016, through July 18, 2016. The sample was composed of 1,303 total participants. Characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1.

All participants were asked about 15 menthol policy items regardless of their smoking status. They were asked to rate their agreement with the items on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating “strongly agree” and 1 indicating “strongly disagree.” To assess participant support for a menthol policy ban, the following information was shared: “The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, is the government organization with the authority to regulate menthol in cigarettes. A panel of scientists has told the FDA that getting rid of menthol cigarettes would reduce the number of people who start smoking.” Then, the following question was asked:

“Based on this information, do you think the FDA should ban menthol flavoring in cigarettes?” Participants had response options of “yes” or “no.”

Results

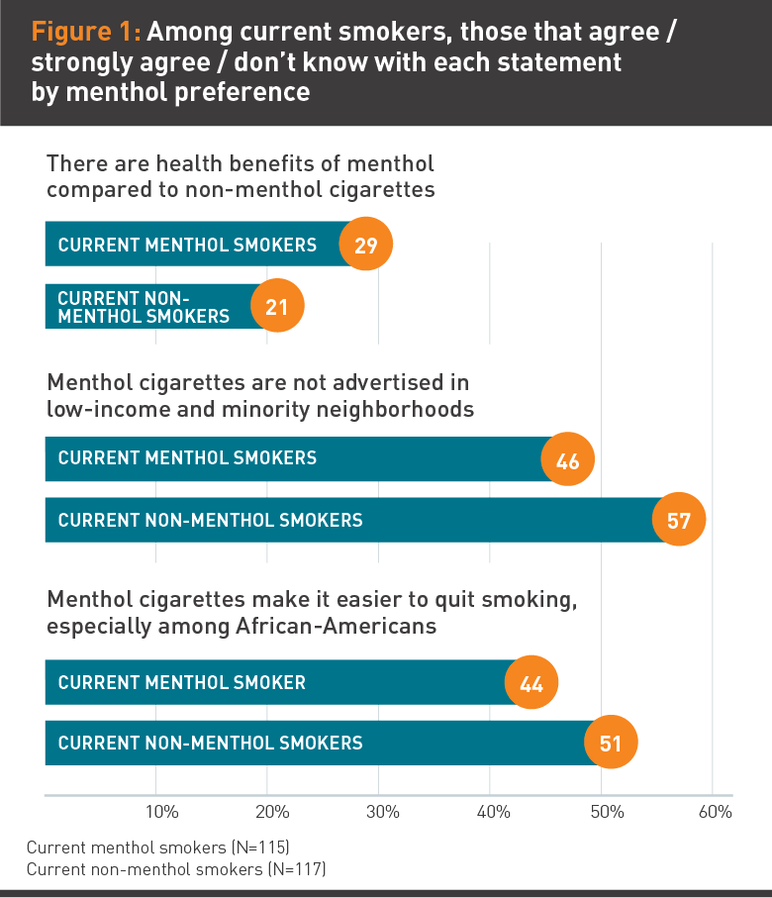

Many respondents misunderstood the role of menthol. These findings were consistent regardless of race, education or menthol smoking status.

- Forty-one percent of respondents incorrectly believed that there were health benefits associated with menthol, compared with non-menthol cigarettes.

- Sixty percent of respondents incorrectly thought that menthol makes it easier to quit smoking, especially among African-Americans.

- Only 36 percent of respondents knew that menthol cigarettes were advertised in low-income and minority neighborhoods.

However, among those with misperceptions, significant demographic differences existed by menthol smoking status (Figure 1), race and education. African-Americans, those who were less educated and non-menthol smokers had more misperceptions about menthol.

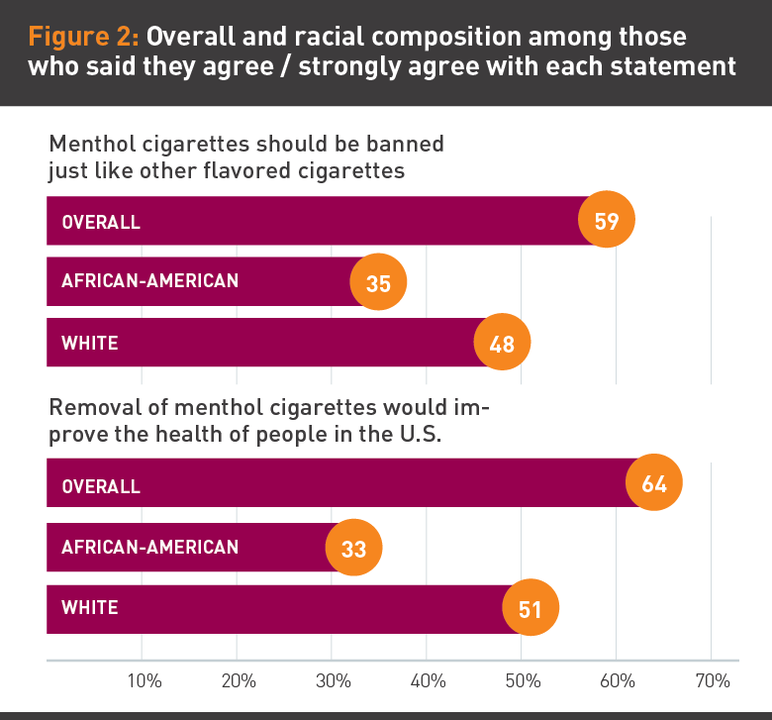

Nearly 60 percent of the sample agreed that menthol should be banned and 64 percent said that removing menthol would improve the health of people in the U.S. Of the 60 percent that agreed that menthol should be banned, 48 percent were white and 35 percent were African-American. Of the 64 percent that agreed that removing menthol cigarettes would improve the health of people in the U.S., 51 percent were white and 33 percent were African-American (Figure 2).

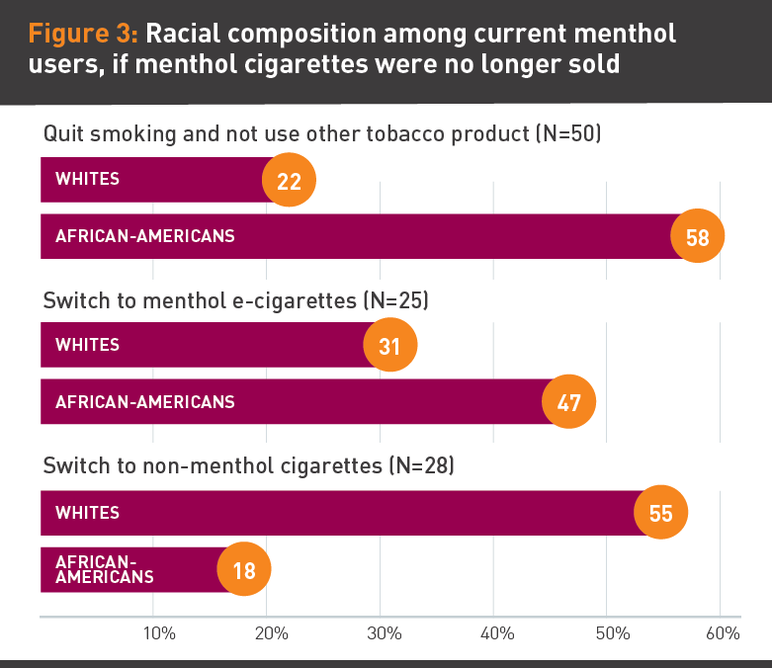

Significantly more white menthol smokers (55 percent) than African-American menthol smokers (18 percent) reported that they would switch to non-menthol cigarettes if a menthol ban existed. Significantly more African-Americans than whites reported that they would quit smoking (58 percent of African-Americans versus 22 percent of whites) or switch to menthol e-cigarettes (47 percent of African-Americans versus 31 percent of whites) (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Our study findings support a menthol ban and indicate that it could urge people to quit smoking. We are encouraged by these results, and the FDA should take notice. The evidence is clear: the FDA must act to get menthol cigarettes and all menthol combustible products off the market to protect public health. States and localities, however, do not have to wait for the FDA to act. We encourage states and local municipalities to prohibit the sale of menthol, mint and wintergreen tobacco products in their communities and protect residents from this deadly product now.

Additionally, although menthol cigarettes are no less dangerous than traditional cigarettes, misunderstandings about menthol persist. African-Americans, who have long been targeted by the tobacco industry, continue to have misperceptions about the health and properties of menthol cigarettes. Until a ban on menthol exists, education is needed regarding menthol cigarettes. We must engage communities in genuine conversations about the impact of menthol cigarettes. The public health community must interact with all population sectors to discuss how the tobacco industry has targeted communities and neighborhoods with menthol cigarettes, and to correct misperceptions.

More in traditional tobacco products

Want support quitting? Join EX Program

By clicking JOIN, you agree to the Terms, Text Message Terms and Privacy Policy.

Msg&Data rates may apply; msgs are automated.