Slim and stylish: How tobacco companies hooked women by “feminizing” cigarettes

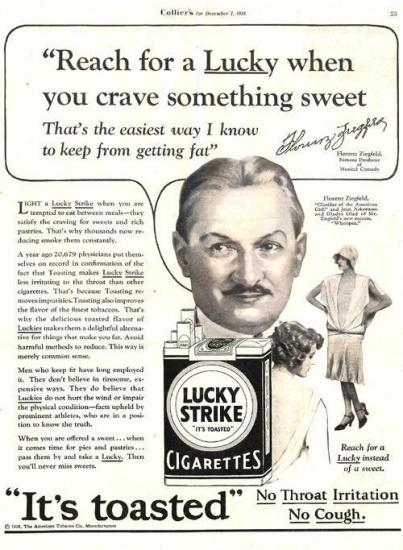

In the 1920s, Lucky Strike unveiled a new advertising campaign that was credited with increasing the brand’s cigarettes sales more than 300 percent in the first year. The slogan: “Reach for a lucky instead of a sweet.”

The ads, “designed to prey on female insecurities about weight and diet,” as the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising put it, helped usher in a wave of tobacco marketing targeted to women. Many of these campaigns strived to entice women to smoke by using mainstream beauty and fashion standards to portray smoking as feminine.

An article published in 2000 in the journal Tobacco Control summarized the marketing shift to target women: “Smoking had to be repositioned as not only respectable but sociable, fashionable, stylish, and feminine.” Featuring attractive, slender women draped in high fashion became a marketing staple. In following years, tobacco companies developed brands marketed as “slim,” “low-tar,” “light” and “ultralight” to tap into these themes.

There are many examples of the tobacco industry targeting women this way. For years, Philip Morris offered promotions for its Virginia Slims cigarettes, including “V wear” catalogues with blouses, coats, scarves and accessories in exchange for purchasing packs of Virginia Slims cigarettes. In 2008, the brand debuted “purse packs”—sleek, chic, compact packs about half the size of a regular pack of cigarettes and sold in “Super Slims Lights” and “Super Slims Ultra Lights.”

American Tobacco Company featured clothing, lighters and even shopping mall guides for its Misty Slims brand. R. J. Reynolds’ catalogues offered cigarette-branded clothing, jewelry, lipstick holders, lighters and other accessories.

R. J. Reynolds introduced Camel No. 9 cigarettes in 2007, reminiscent of a popular women’s fragrance and fashion icon. Camel No. 9 marketing featured hot pink colors, flowers and the slogan “light and luscious.” (The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act banned terms like “low-tar” and “light” without evidence of reduced harm, but not “slim,” which is still prevalent. The act also banned giveaways of branded noncigarette items.)

As these examples show, the tobacco industry has used mainstream fashion and beauty to sell cigarettes for about a century. “Fashion trends change, but tobacco companies’ addiction to manipulating women through these trends has not changed,” reports the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising.

For more on how tobacco companies have targeted women, read about the industry’s marketing strategy of using women’s equality struggles to sell cigarettes.

*Images courtesy of Trinkets & Trash and Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising

More in tobacco industry marketing

Want support quitting? Join EX Program

By clicking JOIN, you agree to the Terms, Text Message Terms and Privacy Policy.

Msg&Data rates may apply; msgs are automated.