Tobacco is a social justice issue: The military

While the overall smoking rate has declined, including a drop among youth to a record low of 6 percent, the numbers don’t tell the whole story. Tobacco use disproportionately affects many populations—including people in low-income communities, racial and ethnic minorities, LGBT individuals, members of the military and those with mental health conditions—who have a long and documented history of being targeted by the tobacco industry.

The plums are here to be plucked.

That’s what a tobacco company wrote in an internal document to describe its new strategy for growing cigarette sales in a promising market: the military. The company, Lorillard, was one of many in the tobacco industry to recognize the military market as an attractive business opportunity in the 1980s. In the 1983 planning document, Lorillard added that “there isn’t a market in the country that has the sales potential for Newport like the military market.”

The tobacco industry saw the military as a desirable prospect for many reasons, including the young adult servicemen, which R.J. Reynolds described as “less educated,” “part of the wrong crowd” and “classic downscale smoker” in a marketing strategy plan called “MILITARY YAS INITIATIVE.” Tobacco companies know it’s essential to get people hooked on their products while they’re young. Young adults are the most at-risk of tobacco addiction, and almost all smokers—99 percent—start by age 26.

It’s no coincidence that military service members, like other groups profiled by the tobacco industry, smoke at higher rates than the general population. While the tobacco industry positions smoking as consumer choice, evidence reveals a specific and strategic pattern of exploitation.

Making the Military a Marketing Priority

Industry documents show that the tobacco industry targeted military personnel in the 1980s with cigarette marketing and branded giveaways, especially at sponsored and promotional events. Tobacco company Brown & Williamson is one example. In 1981, B&W expanded its Kool Jazz Festivals to military bases, and sponsored Kool Super Nights concerts and other events at base clubs. These events featured B&W-branded items such as keychains, notebooks and napkins that the company hoped would “be around long after each concert and thus serve as a reminder of Kool’s sponsorship.”

Lorillard relied on promotional events like the “Newport Military Challenge,” which was organized at base fairs and picnics, and included activities such as tug-of-war, milk chugging and dance contests. Another Newport program parked a van on base—frequently in front of the base store—and distributed free cigarettes or coupons.

The tobacco industry even saw an opportunity to target the families of military personnel, including sponsoring events at military wives’ clubs and advertising in the free on-base magazines. For example, B&W promoted its brand at bingo nights on military bases in 1982, where it provided bingo cards and chips. Bingo participants received cigarettes, coupons, matches and catalogs.

Smoking in the Military

In 2011, nearly a quarter—24 percent—of active duty military personnel reported smoking cigarettes, compared to 19 percent of civilians at that time.

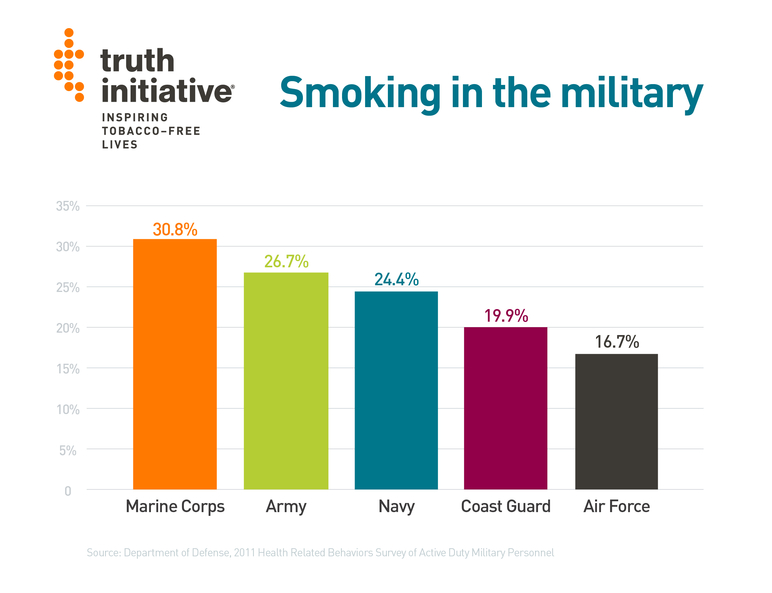

Smoking prevalence among troops varies by age and service. Young enlistees smoke at significantly higher rates than commissioned officers, and according to a 2011 report from the U.S. Department of Defense, the Marines have the highest rate of smoking among all service members at 30.8 percent.

A lot of troops didn’t smoke before joining the military. In fact, 38 percent of military smokers start after enlisting, which raises the question: Does joining the military lead service members to smoke?

While there is a smoking ban during basic training and the DoD prohibits smoking in workplace buildings and vehicles, other tobacco policies and their enforcement vary across each service, and even then, from installation to installation. For example, a policy on one Army installation accommodates members to allow them to smoke inside buildings by making smoking preferences a determining factor in room assignments. On the other hand, a policy at an Air Force base restricts smoking to “designated tobacco use areas.” The Air Force and the Navy have stronger policies, which may account for their slightly lower smoking rates compared to other services.

Until recently, tobacco products on military bases could be sold at prices 5 percent below local prices. However, one study found that discounts were often much more than that, with as much as a 73 percent discount and an average discount rate of 25 percent on base, compared to the prices at surrounding stores off-base. Now, tobacco products in military resale outlets can’t be sold at prices less than the most competitive price in the local community.

Access to cheap tobacco products, differing policies and other factors may contribute to initiation, a pro-tobacco culture and higher smoking rates in the military.

The Effects on Military Performance

Smoking harms health, but for military members, it also harms readiness and performance—meaning how effective they are in completing a mission or task. Smoking puts the safety of troops at risk because tobacco use damages respiratory health and cardiac fitness, even in the short term. Smoking also impairs night vision and slows wound healing.

Several research studies and military physical training tests show that, compared with nonsmokers, troops who smoke have:

- a lower physical performance capacity;

- higher odds of being injured;

- a higher risk of being hospitalized (for causes other than injury or pregnancy); and

- a higher number of lost workdays per year due to illnesses, alcohol and substance use and accidents.

Tobacco use in the military also comes with a hefty price. The DoD spends more than $1.6 billion each year on tobacco-related medical care, increased hospitalization and lost days of work. It has also been estimated that $2.7 billion in Veterans Health Administration health care expenditures are due to the health effects of smoking.

More in targeted communities

Want support quitting? Join EX Program

By clicking JOIN, you agree to the Terms, Text Message Terms and Privacy Policy.

Msg&Data rates may apply; msgs are automated.