From social taboo to target market: How tobacco use became a women’s issue

Something interesting happened after the U.S. Surgeon General issued a report confirming the link between smoking and cancer in 1964.

In the years following the release of the report, the smoking rate among men dropped from 52 percent to 38 percent between 1965 and 1979. The percentage of women smoking cigarettes, however, saw a much less significant drop. During that same time period, the smoking rate for women decreased from 34 to 30 percent.

How did smoking, which used to be socially unacceptable for women, become almost as common among women as men? The 2014 Surgeon General’s report, released 50 years after the first report, points to one major factor: “Smoking prevalence among women … continued to increase across the 1970s as products were aggressively marketed to women.”

A target market

As early as the 1920s, tobacco companies began to appeal to women through advertising. One of the best-known efforts is the American Tobacco Company’s “Reach for A Lucky Instead of a Sweet” campaign for its Lucky Strikes cigarettes.

The industry also began to link smoking with women’s liberation. A well-known example is the time a tobacco company organized a group of women to march (reminiscent of suffrage marches) holding cigarettes in New York City for the Easter parade. The cigarettes were referred to as “torches of freedom” to help transform the public perception of smoking as a social taboo for women.

New targeted marketing campaigns emerged in the decades that followed, many using themes of fashion and beauty. In the late 1960s, brands developed specifically for women entered the market, beginning with Virginia Slims and its slogan that tapped into the women’s liberation movement: “You’ve come a long way, baby.” Companies introduced other brands for women such as Eve and Silva Thins. These brands had a big influence: Six years after Virginia Slims hit the market, the smoking initiation rate among 12-year-old girls had increased by 110 percent.

Even more recently, the tobacco industry makes niche brands and targets marketing campaigns to women. An example from 2007: R.J. Reynolds introduced a cigarette brand called Camel No. 9, a name evocative of designer perfume and women’s fashion. A study by the University of California at San Diego and Truth Initiative® found that the brand may have been effective in encouraging young girls to start smoking, with teen girls citing it as a favorite cigarette campaign.

Smoking rates among women

Although data show overall cigarette use has declined in the U.S., they also highlight disparities in smoking rates. For example, overall smoking rates have not declined as quickly for women as for men. Since 1970, smoking rates among women have dropped by about 30 percent, compared to a 40 percent drop among men.

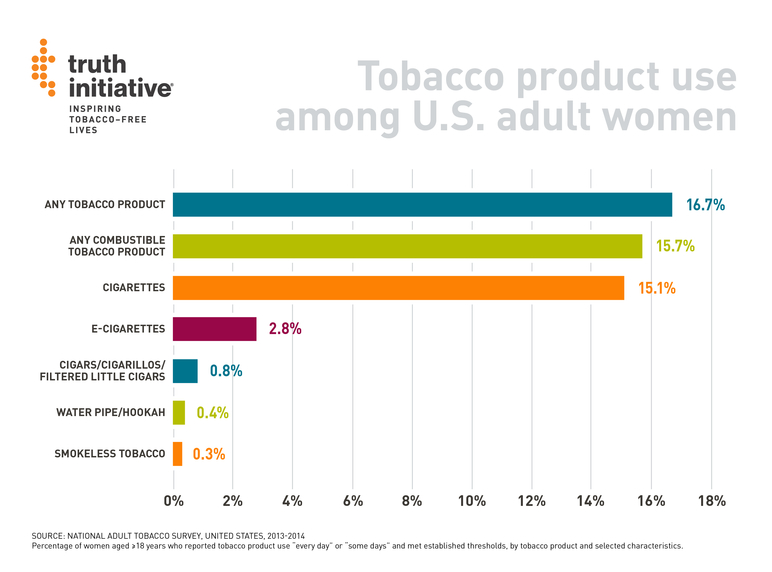

According to a recent CDC report, 13.6 percent of women smoke cigarettes and 16.7 percent of women use any tobacco product.

Smoking rates among women also vary by factors such as education level and income. Smoking rates are highest among women who earned a GED diploma, at 44.7 percent, while the percentage of college graduates and women with a graduate degree who smoke are in the single digits. About 28 percent of women below the poverty level smoke compared to 16.7 percent of women at or above the poverty level.

Health Effects

Each year, more than 200,000 women die of tobacco-related diseases. The Surgeon General’s report in 2014 also found that the risks for women smokers has risen dramatically—in fact, the risk of death from any cause has more than tripled in women smokers in the last 50 years.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women (and men), and smoking causes 80 to 90 percent of all lung cancer deaths. An estimated 71,280 women will die from lung cancer in 2017.

Heart disease, including heart attacks and strokes, is the overall leading cause of death among women, killing about 300,000 of them each year. Smoking is a leading cause of heart disease and accounts for 1 of every 3 deaths from heart disease. Women smokers have a higher risk of getting heart disease than men.

Women who smoke risk other consequences, including reproductive health effects like menstrual problems, decreased fertility and premature menopause.

Smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke among pregnant women are a major cause of complications like spontaneous abortions, stillbirths and sudden infant death syndrome after birth. They also increase the risk of low-birth-weight babies and premature delivery.

Still, approximately 1 in 10 pregnant women smoke during the last month three months of pregnancy—and it has an impact on the health of their children, too.

The children of pregnant women who smoke are at risk for developmental and behavioral problems, including leukemia, abnormal blood pressure, respiratory disorders, eye problems and attention deficit disorder. Smoking is also known to cause ectopic pregnancy, which is a condition that the fetus rarely survives and is potentially fatal for the mother.

For more on how tobacco disproportionately affects certain populations—including people in low-income communities, racial and ethnic minorities, LGBT individuals and those with mental illness—read our collection of stories about how tobacco is a social justice issue.

More in targeted communities

Want support quitting? Join EX Program

By clicking JOIN, you agree to the Terms, Text Message Terms and Privacy Policy.

Msg&Data rates may apply; msgs are automated.